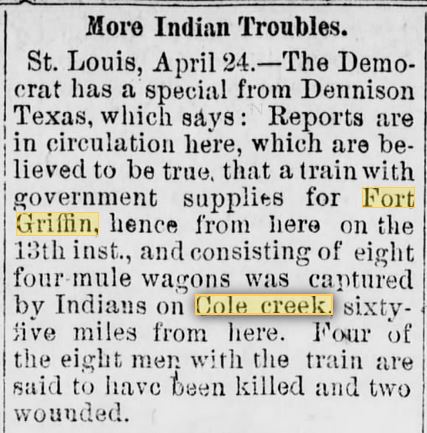

Late last week, a reader asked me if the Red River had ever served as a boundary between the United States and Mexico prior to Texas becoming a Republic in 1836

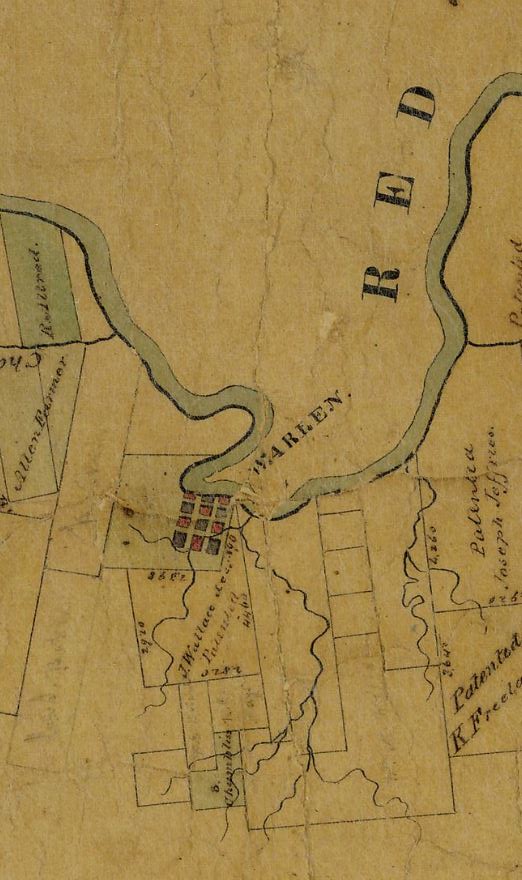

Between 1803 (when the U.S. purchased the Louisiana Territory) and 1819 (before Mexico became its own republic), the Red River was the border between New Spain and the United States north of the Great Raft… kind of. Filibustering Anglos and Native people who were forcefully displaced by the United States populated the Red River area above the Great Raft and down the Sabine River. The absence of troops, abandonment of forts, and the lack of good surveys marked the region essentially a “no man’s land.”

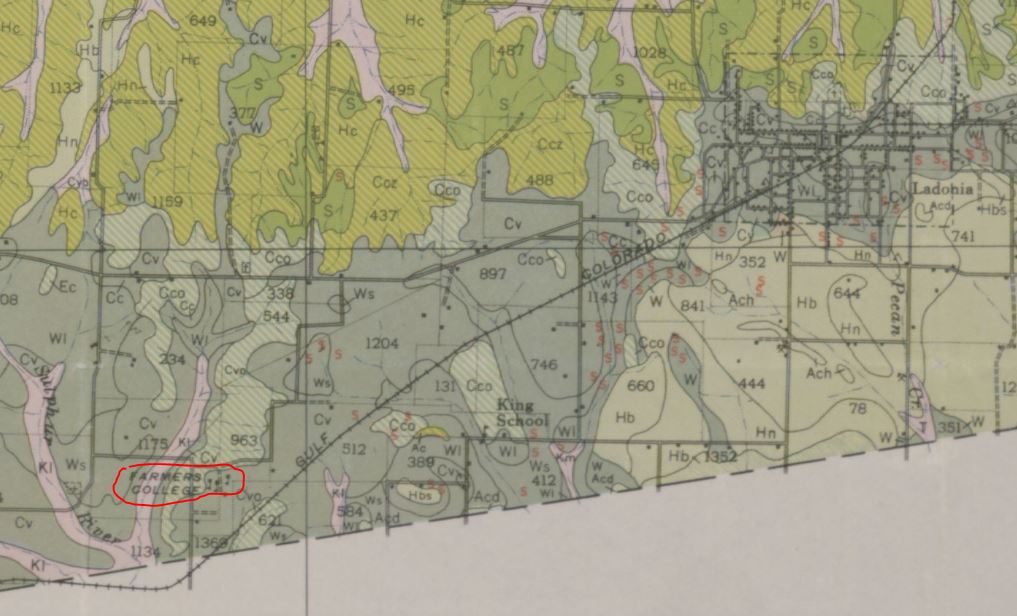

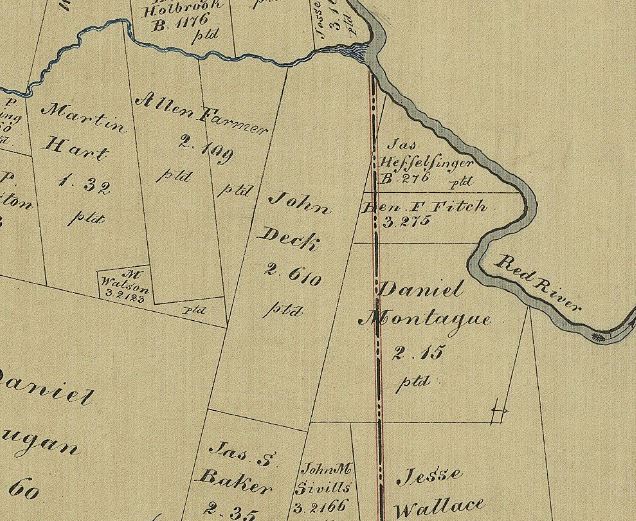

This all had to do with the fact that the Red River emptied into the Mississippi River, the southern-most major river to do so. It promised to become an important trade route, with the assumption that it could carry goods from New Orleans all the way to Santa Fe. Since the Louisiana Purchase included the entire watershed of the Mississippi River, the U.S. had full claim to the river. But the Spanish claimed a portion of the Sulphur River, a tributary of the Red River, because its flow was south of the Red River.

Spain was tiring of its boundary problems with the U.S., and not just around the Red River. Florida, still a Spanish possession, was being inundated by filibusterers, escaped people who had been enslaved, dispossessed tribes, continuous threats of invasion by Britain and pirates, and occasional U.S. military invasions, too.

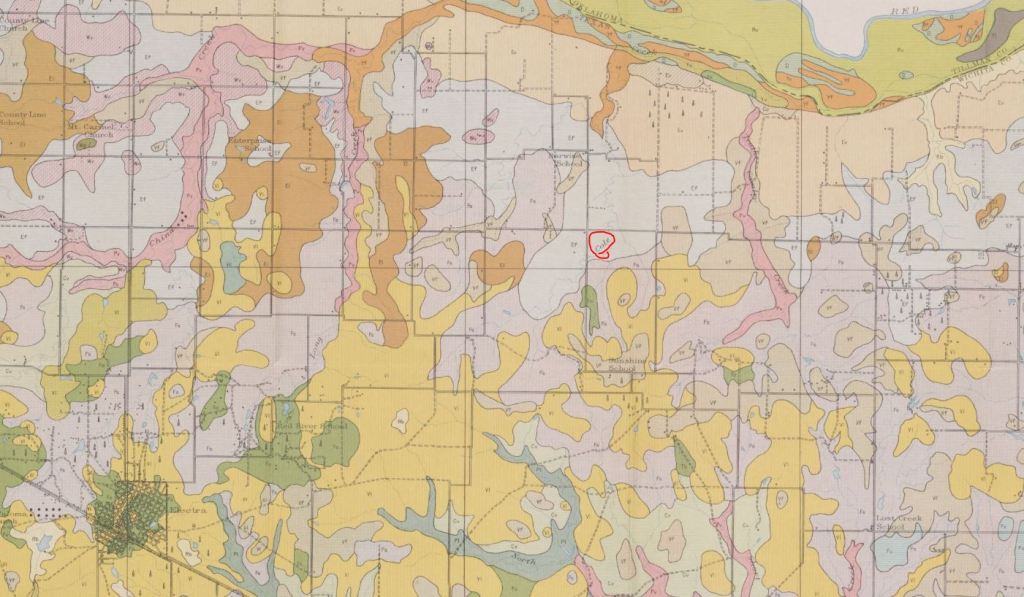

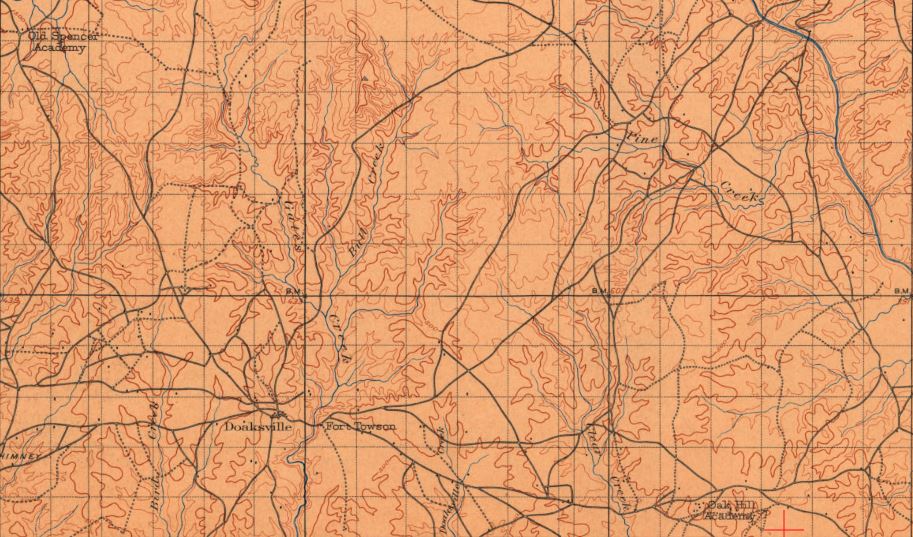

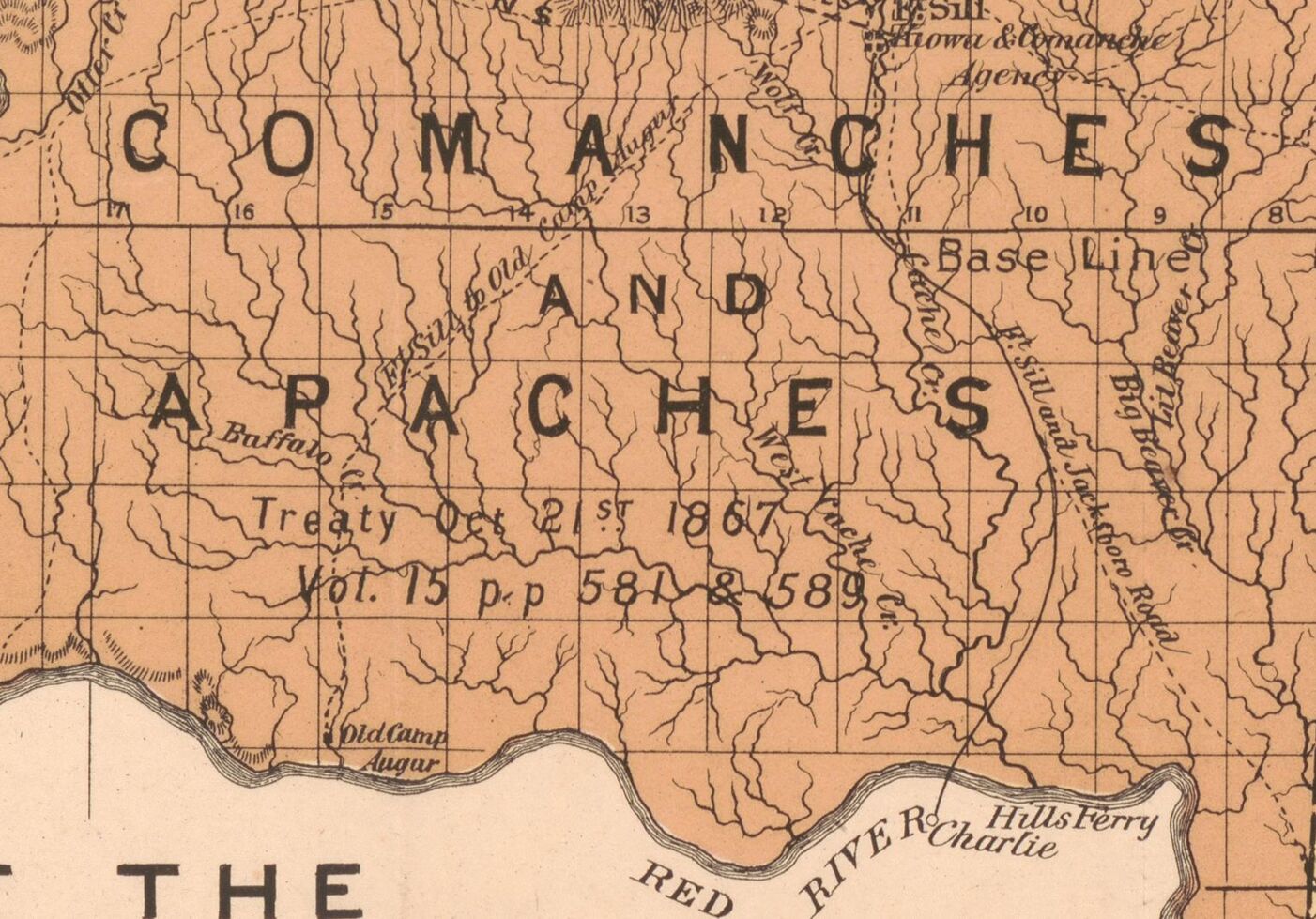

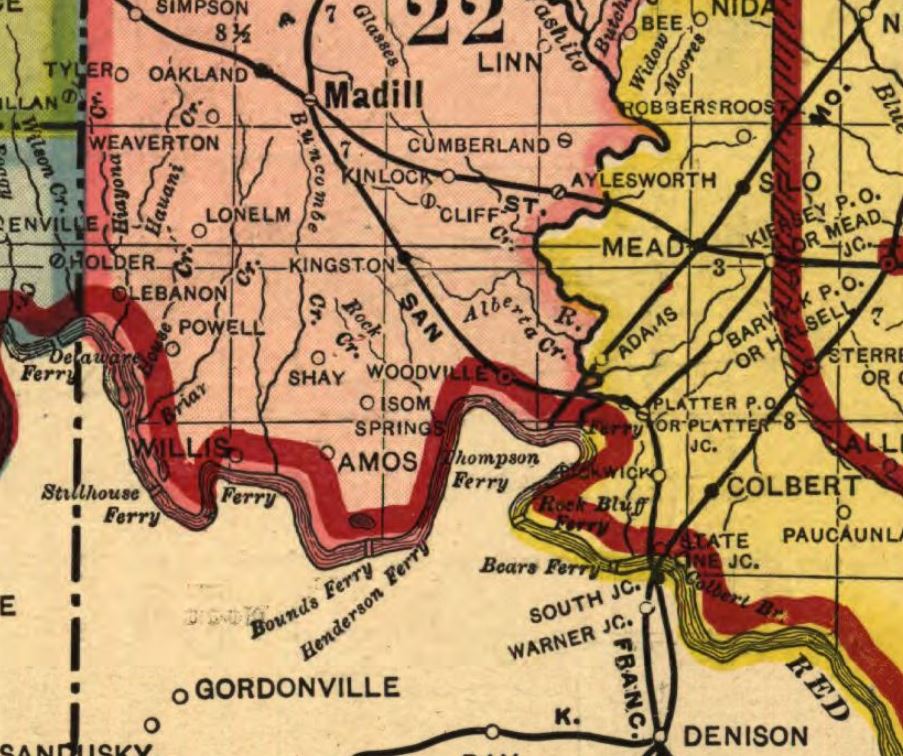

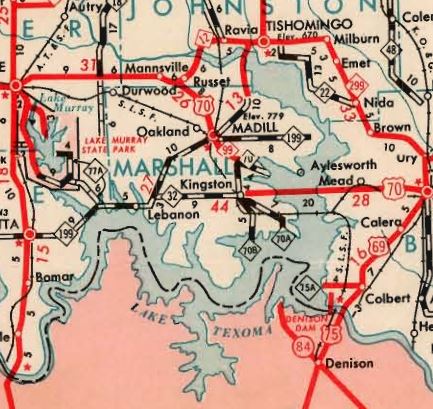

So, the United States saw an opportunity. In the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, negotiated by John Quincy Adams, Secretary of State in the James Monroe administration, the United States promised Spain that it would not interfere with Spain’s claims below the Red River, but that the Great Bend area would become part of the United States. To mark this boundary, an imaginary line was drawn south from the Red River to the 32nd parallel along the 18th Meridian (from Washington, D.C., not Greenwich). This is now known as the Index Line. In addition, the U.S. gave Spain some much-needed cash and Spain gave away Florida. Spain asserted its claims on today’s Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, parts of Colorado, and California.

But that’s not all!

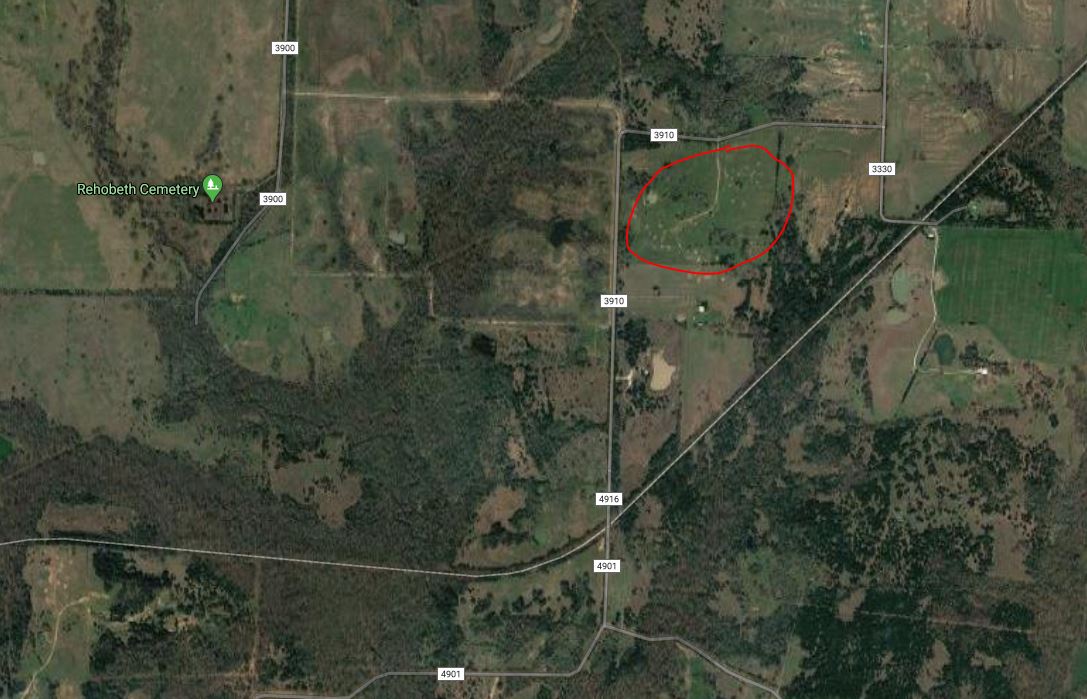

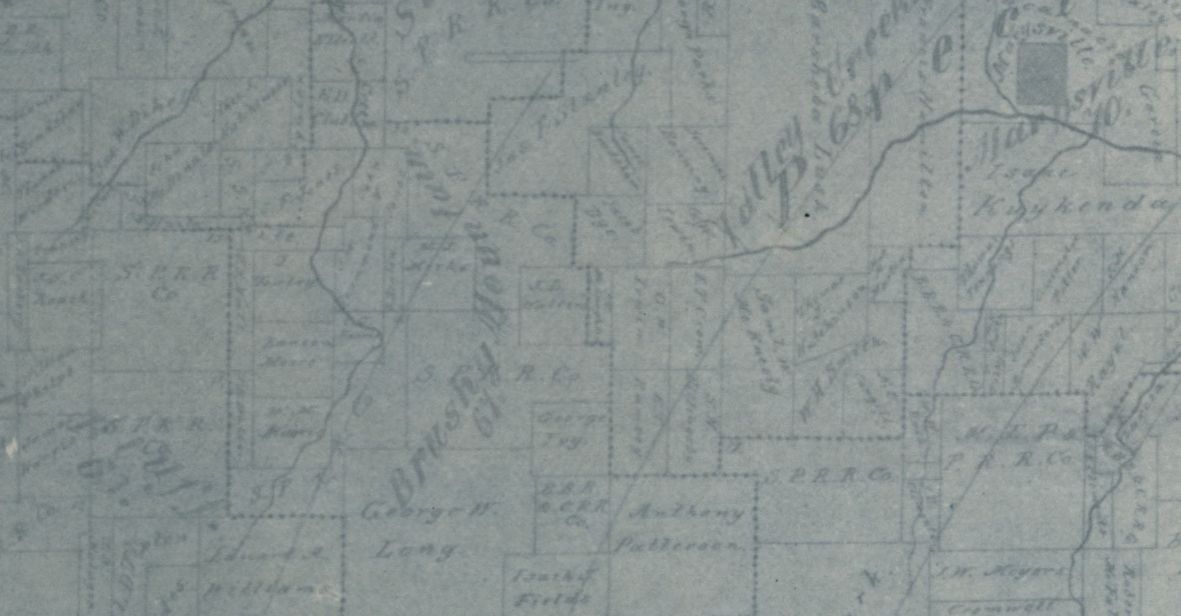

Around 1821, Spanish Texas became Mexican Texas. The Anglos who filibustered south of the Red River beyond the Index Line showed dual loyalties: they claimed to be Mexicans who needed military assistance when the U.S. tried to impose taxes, and they claimed to be U.S. citizens needing military assistance when Mexico allowed displaced native tribes to settle in the region. This is why the “proposed boundary of Arkansas” on this 1835 map extends to the 19th Meridian and 33rd parallel… the Anglos at Jonesboro (in today’s Red River County, TX) and south of Pecan Point (today’s McCurtain County, OK) claimed this portion of Mexico for the U.S. once Fort Towson (today’s Choctaw County, OK) was established in 1824.